Much of what ultimately became Czechoslovakia back in 1919 had been part of the recently defeated Austro-Hungarian Empire where many cities and towns went by German names. After the First World War ethnic Germans in the Sudeten border districts resisted taking on Czech names for their cities. Rather than switch back and forth between two names for the same places, the novel uses the German names for these Sudeten municipalities. But to make it easier for readers to find cities mentioned in the book, following is a guide to the names used today:

Much of what ultimately became Czechoslovakia back in 1919 had been part of the recently defeated Austro-Hungarian Empire where many cities and towns went by German names. After the First World War ethnic Germans in the Sudeten border districts resisted taking on Czech names for their cities. Rather than switch back and forth between two names for the same places, the novel uses the German names for these Sudeten municipalities. But to make it easier for readers to find cities mentioned in the book, following is a guide to the names used today:

Read On

Sudetenland is the premiere novel by George T. Chronis. The book delivers suspenseful and sweeping historical fiction set against Central European intrigue during the late 1930s leading up to 1938’s Munich Conference. Having swallowed up Austria, Adolph Hitler now covets Czechoslovak territory. Only France has the power to stand beside the government in Prague against Germany… but will she? The characters are the smart and sometimes wise-cracking men and women of this era – the foreign correspondents, intelligence officers, diplomats and career military – who are on the front lines of that decade’s most dangerous political crisis. If Czechoslovak president Edvard Beneš ignores the advice of French premier Édouard Daladier and refuses to give up Bohemian territory willingly, then Hitler orders that it be taken by force. The novel takes readers behind the scenes into the deliberations and high drama taking place within major European capitals such as Prague, Paris, Berlin, Vienna and London as the continent hurtles toward the crucible of a shooting war.

Read On

During conversation, characters in Sudetenland© will often use terms from their own languages to describe something. This is especially true of military ranks. Although exposition in the book will use the English version of a rank nearby when a character uses the domestic term, for those of you who wish to look at a handy reference you can find it here on the website. Following are the Československá Armáda military ranks:

During conversation, characters in Sudetenland© will often use terms from their own languages to describe something. This is especially true of military ranks. Although exposition in the book will use the English version of a rank nearby when a character uses the domestic term, for those of you who wish to look at a handy reference you can find it here on the website. Following are the Československá Armáda military ranks:

Read On

During conversation, many characters in Sudetenland© will often use terms from their own languages to describe something. This is especially true of military ranks. Although exposition in the book will use the English version of a rank nearby when a character uses the domestic term, for those of you who wish to look at a handy reference you can find it here on the website. Following are the military ranks of the Deutsch Heer:

During conversation, many characters in Sudetenland© will often use terms from their own languages to describe something. This is especially true of military ranks. Although exposition in the book will use the English version of a rank nearby when a character uses the domestic term, for those of you who wish to look at a handy reference you can find it here on the website. Following are the military ranks of the Deutsch Heer:

Read On

During conversation, many characters in Sudetenland© will often use terms from their own languages to describe something. This is especially true of military ranks. Although exposition in the book will use the English version of a rank nearby when a character uses the domestic term, for those of you who wish to look at a handy reference you can find it here on the website. Following are the military ranks of the Schutzstaffel:

During conversation, many characters in Sudetenland© will often use terms from their own languages to describe something. This is especially true of military ranks. Although exposition in the book will use the English version of a rank nearby when a character uses the domestic term, for those of you who wish to look at a handy reference you can find it here on the website. Following are the military ranks of the Schutzstaffel:

Read On

T.G. Maseryk.

Czechoslovakia was a nation carved out of the Austro-Hungarian Empire in the aftermath of the First World War. Austria had been on the losing side of the conflict and included territories populated by a dizzying multitude of ethnic nationalities. In a speech for the U.S. Congress in January of 1918, President Woodrow Wilson had put forth Fourteen Points as aims for the Allies to conclude the war and achieve peace in the world thereafter. Point No. 10 was the call for all peoples living in Austria-Hungary to be accorded the freest opportunity to autonomous development. When Austria’s principal ally, Imperial Germany, determined that disaster on the battlefield was imminent, the Germans initiated negotiations in early October of that year to end the war based on Wilson’s Fourteen Points:

Read On

During conversation, many characters in Sudetenland© will often use terms from their own languages to describe something. This is especially true of military ranks. Although exposition in the book will use the English version of a rank nearby when a character uses the domestic term, for those of you who wish to look at a handy reference you can find it here on the website. Following are the military ranks of the Armée de Terre:

During conversation, many characters in Sudetenland© will often use terms from their own languages to describe something. This is especially true of military ranks. Although exposition in the book will use the English version of a rank nearby when a character uses the domestic term, for those of you who wish to look at a handy reference you can find it here on the website. Following are the military ranks of the Armée de Terre:

Read On

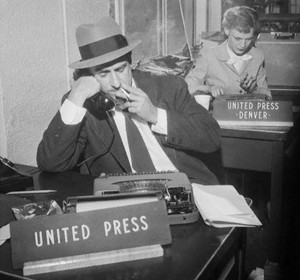

News services have been around since the 1850s as telegraph technology was introduced and enhanced. Especially in the United States during the latter half of the 19th Century, the growth of urban centers saw a huge demand for newspapers. Well into the 20th Century many large cities supported multiple morning and evening newspapers. All of these broadsheets and tabloids created an insatiable appetite for national and international news coverage that wire news services stepped up to serve. Thanks to the arrival of teletypewriter technology, wire service reporters working out of bureaus in key cities worldwide competed to get major stories covered and out to their subscribers first. Some services such as the Associated Press have their own reporters but are also collectives where member news organizations pool their coverage. Other organizations such as United Press, Reuters and International News were subscription based where news generated by the wire service correspondents were delivered to newspapers for a fee. With the advent of radio, and later television, the demand for more news from far-flung parts of the world continued to increase.

News services have been around since the 1850s as telegraph technology was introduced and enhanced. Especially in the United States during the latter half of the 19th Century, the growth of urban centers saw a huge demand for newspapers. Well into the 20th Century many large cities supported multiple morning and evening newspapers. All of these broadsheets and tabloids created an insatiable appetite for national and international news coverage that wire news services stepped up to serve. Thanks to the arrival of teletypewriter technology, wire service reporters working out of bureaus in key cities worldwide competed to get major stories covered and out to their subscribers first. Some services such as the Associated Press have their own reporters but are also collectives where member news organizations pool their coverage. Other organizations such as United Press, Reuters and International News were subscription based where news generated by the wire service correspondents were delivered to newspapers for a fee. With the advent of radio, and later television, the demand for more news from far-flung parts of the world continued to increase.

Read On

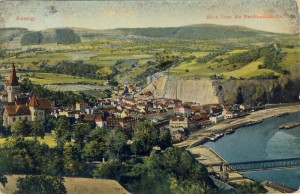

Best known as the home of the huge Škoda Works armaments conglomerate and the famous Měšťansky Pivovar (Pilsner Urquell Brewery), Plzeň was the second largest city in Czechoslovakia at the time of the Sudetenland crisis. With deposits of coal and iron ore nearby the city became an early center of industry. Plzeň is strategically located in Western Bohemia with a major rail junction and access to four rivers. The city is also situated on the old trade route to Bavaria, which makes Plzeň a stepping stone to Prague. These growing transportation networks drew many Czechs to the city during the 19th Century. By the 1930s most ethnic Germans in the area lived outside Plzeň.

Best known as the home of the huge Škoda Works armaments conglomerate and the famous Měšťansky Pivovar (Pilsner Urquell Brewery), Plzeň was the second largest city in Czechoslovakia at the time of the Sudetenland crisis. With deposits of coal and iron ore nearby the city became an early center of industry. Plzeň is strategically located in Western Bohemia with a major rail junction and access to four rivers. The city is also situated on the old trade route to Bavaria, which makes Plzeň a stepping stone to Prague. These growing transportation networks drew many Czechs to the city during the 19th Century. By the 1930s most ethnic Germans in the area lived outside Plzeň.

Read On

The Austrians have ruled Graz and the surrounding area since the 12th Century. The city is today the second largest in Austria. Situated in the southeastern portion of the country, Graz is the capital of the federal state of Styria. The city lies in a valley surrounded by mountains southeast of the Alps and straddles the Mur River. Since the community is shielded from northern air flows the temperature is warmer than most cities in the country with more sunshine and less rain. For these reasons Graz had already become a destination for retirees by the time railroads arrived in 1844, followed soon thereafter by industrialization. As the city grew more wealthy influential citizens began funding the construction of important institutions including universities such as Karl-Franzens-Universität where Johannes Kepler was a professor of mathematics, and Technische Universität Graz where Nikola Tesla studied electrical engineering for a while. At the time of the Sudeten Crisis, the national socialist movement was deeply rooted within the universities, prominent neighborhoods and the civll service in Graz.

The Austrians have ruled Graz and the surrounding area since the 12th Century. The city is today the second largest in Austria. Situated in the southeastern portion of the country, Graz is the capital of the federal state of Styria. The city lies in a valley surrounded by mountains southeast of the Alps and straddles the Mur River. Since the community is shielded from northern air flows the temperature is warmer than most cities in the country with more sunshine and less rain. For these reasons Graz had already become a destination for retirees by the time railroads arrived in 1844, followed soon thereafter by industrialization. As the city grew more wealthy influential citizens began funding the construction of important institutions including universities such as Karl-Franzens-Universität where Johannes Kepler was a professor of mathematics, and Technische Universität Graz where Nikola Tesla studied electrical engineering for a while. At the time of the Sudeten Crisis, the national socialist movement was deeply rooted within the universities, prominent neighborhoods and the civll service in Graz.

Read On

Soon after Czechoslovakia had gained independence it became obvious that the country had long borders to defend against many unfriendly neighbors. Germany, Poland and Hungary were all viewed with suspicion with only Romania considered to be friendly. When Adolph Hitler came to power in Germany during 1933 the government in Prague decided to ring its borders with defensive fortifications. The first stage of construction started in 1934, and had the intended program had gone on uninterrupted the fortification lines would not have been completed until the 1950s. The French shared their design blueprints for the Maginot Line, which the Czechs adapted and enhanced for their own needs:

Soon after Czechoslovakia had gained independence it became obvious that the country had long borders to defend against many unfriendly neighbors. Germany, Poland and Hungary were all viewed with suspicion with only Romania considered to be friendly. When Adolph Hitler came to power in Germany during 1933 the government in Prague decided to ring its borders with defensive fortifications. The first stage of construction started in 1934, and had the intended program had gone on uninterrupted the fortification lines would not have been completed until the 1950s. The French shared their design blueprints for the Maginot Line, which the Czechs adapted and enhanced for their own needs:

Read On

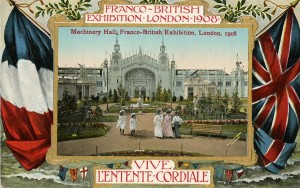

The “cordial understanding” was a declaration signed by France and Great Britain in 1904. After 1,000 years of often fierce competition both nations realized their interests had grown to become very complementary, especially in view of the rise of Imperial Germany. The Entente Cordiale was a settling of colonial disagreements in Africa, the Middle East and Asia. Both Great Britain and France acknowledged their respective holdings and agreed not to undermine the colonial authority of the other. The Entente Cordiale was neither a military or economic alliance between the two Empires. There were no stipulations binding one to the other. The Entente Cordiale was, however, an expression of joint interests that came to define the relationship between Paris and London. So while the Unite Kingdom was under no obligation to go to war with France if the latter came to blows with Germany in 1938, both governments felt it in their best interests to work together.

The “cordial understanding” was a declaration signed by France and Great Britain in 1904. After 1,000 years of often fierce competition both nations realized their interests had grown to become very complementary, especially in view of the rise of Imperial Germany. The Entente Cordiale was a settling of colonial disagreements in Africa, the Middle East and Asia. Both Great Britain and France acknowledged their respective holdings and agreed not to undermine the colonial authority of the other. The Entente Cordiale was neither a military or economic alliance between the two Empires. There were no stipulations binding one to the other. The Entente Cordiale was, however, an expression of joint interests that came to define the relationship between Paris and London. So while the Unite Kingdom was under no obligation to go to war with France if the latter came to blows with Germany in 1938, both governments felt it in their best interests to work together.

Read On

The tradition of sending military officers along with ambassadors in foreign capitals is a long one. For example, the picture at left is German military attaché Captain Adolf von Tiedemann in 1898 after the Battle of Omdurman in the Sudan. These officers were best equipped to accurately evaluate the armed forces in the host countries and report back what they had seen to their superiors. During the first half of the 20th Century most European attachés were colonels or generals. In United States service most career-driven officers saw posting as an attaché to be a dead end, which often resulted in having to go down the list of candidates to find a major or captain who would take the job.

Read On

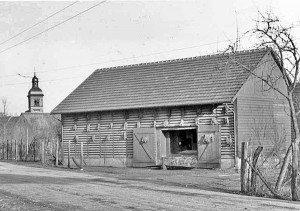

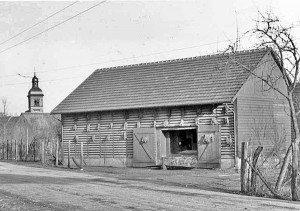

To block the main French invasion route through the Saar to the Rhine, Germany began construction of a fortification line in 1936 after reoccupying the Rhineland. Most of the early emplacements were built under the direction of the army along the Saar River opposite France’s Maginot Line. By early 1938, Chancellor Adolph Hitler grew impatient with the slow progress of construction and ordered the project taken over by Organization Todt, which had been building new highways on schedule all over Germany. With plans to extend what became known as the Westwall from the Swiss border to the Netherlands, Todt amassed 600,000 workers to construct 14,800 bunkers, 5,800 casemates for artillery, plus 2,300 pillboxes for machine guns and anti-tank guns. Unlike the French, there was not time to build these emplacements under ground, so use was made of above ground camouflage and subterfuge. Mass-produced fake barns (like the one pictured above) and village structures were placed at regular junctures along the line. In addition, huge bands of minefields, concrete dragons teeth and tank traps were sown. Despite the huge effort, by the fall of 1938 large swaths of the Westwall were incomplete, and the city of Saarbrücken was left outside of the line.

To block the main French invasion route through the Saar to the Rhine, Germany began construction of a fortification line in 1936 after reoccupying the Rhineland. Most of the early emplacements were built under the direction of the army along the Saar River opposite France’s Maginot Line. By early 1938, Chancellor Adolph Hitler grew impatient with the slow progress of construction and ordered the project taken over by Organization Todt, which had been building new highways on schedule all over Germany. With plans to extend what became known as the Westwall from the Swiss border to the Netherlands, Todt amassed 600,000 workers to construct 14,800 bunkers, 5,800 casemates for artillery, plus 2,300 pillboxes for machine guns and anti-tank guns. Unlike the French, there was not time to build these emplacements under ground, so use was made of above ground camouflage and subterfuge. Mass-produced fake barns (like the one pictured above) and village structures were placed at regular junctures along the line. In addition, huge bands of minefields, concrete dragons teeth and tank traps were sown. Despite the huge effort, by the fall of 1938 large swaths of the Westwall were incomplete, and the city of Saarbrücken was left outside of the line.

Read On

Anyone looking to read more about the 1938 Sudeten Crisis will enjoy picking up Berlin Diary (1941) by William Shirer. He was a journalist who worked for Hearst and went on to be one of Edward R. Murrow’s radio broadcasters in Europe with CBS. During 1938, Shirer was on the scene in Vienna, Prague and Berlin when he broadcasted back home to the United States. The book is full of tremendous first-person observations and anecdotes that are as colorful as they are informative. One plus is Berlin Diary has been reprinted so many times over the years that it is easy to find a copy for not a lot of money.

Anyone looking to read more about the 1938 Sudeten Crisis will enjoy picking up Berlin Diary (1941) by William Shirer. He was a journalist who worked for Hearst and went on to be one of Edward R. Murrow’s radio broadcasters in Europe with CBS. During 1938, Shirer was on the scene in Vienna, Prague and Berlin when he broadcasted back home to the United States. The book is full of tremendous first-person observations and anecdotes that are as colorful as they are informative. One plus is Berlin Diary has been reprinted so many times over the years that it is easy to find a copy for not a lot of money.

Read On

Much of what ultimately became Czechoslovakia back in 1919 had been part of the recently defeated Austro-Hungarian Empire where many cities and towns went by German names. After the First World War ethnic Germans in the Sudeten border districts resisted taking on Czech names for their cities. Rather than switch back and forth between two names for the same places, the novel uses the German names for these Sudeten municipalities. But to make it easier for readers to find cities mentioned in the book, following is a guide to the names used today:

Much of what ultimately became Czechoslovakia back in 1919 had been part of the recently defeated Austro-Hungarian Empire where many cities and towns went by German names. After the First World War ethnic Germans in the Sudeten border districts resisted taking on Czech names for their cities. Rather than switch back and forth between two names for the same places, the novel uses the German names for these Sudeten municipalities. But to make it easier for readers to find cities mentioned in the book, following is a guide to the names used today: